One of my favorite ways to write non-fiction is what I like to call faction. By that I mean it’s a fictional story in which all of the characters and the details are based on real facts.

One example is ANIMAL SCAVENGERS: WOLVERINES (Lerner, 2005) which was selected as a Children’s Book Council and International Reading Association Children’s Choice Book for 2006.

WOLVERINES

tells the story of one gutsy female wolverine living in a forest in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains in northern Canada. The female wolverine is a fictional character. However, the story of her life shares real facts about wolverines and the rugged habitat they call home.

In the story, the wolverine even has a narrow escape from a bear that attacks in an attempt to get a share of the leftovers she’s claimed from a wolf pack.

And, come spring, this story moves on to the birth of her two babies, a little male and a little female, and how she raises them.

Adding to the challenge of telling this fictional, fact-based story, WOLVERINES is a photo essay so all the illustrations are real photos. To find these, I looked at thousands of photos. I contacted experts who study wolverines in the field and take photos. I also did on-line searches of professional photo agencies (stock shops). The challenge was to find just the right images to portray the fictional action. I also had to find images of wolverines that looked the right age and had fur with similar-enough coloring and markings to appear to be the same animal. In fact, this faction story is illustrated with images of a number of different unrelated wolverines.

HIP-POCKET PAPA (Charlesbridge, 2010) is an example of faction illustrated by an artist. It was honored with four awards, including being named a 2011 Charlotte Zolotow Award Honor Book. I was thrilled to receive this award because it’s for writing excellence in a picture book.

HIP-POCKET PAPA tells the fictional story of a real frog, a very rare tiny frog. It's unusual because the males carry the teeny, tiny tadpoles in hidden pockets on their hips.

It was a chance to let my imagination run—as long as I kept the animals and the place real because the illustrator could show whatever I described. So I was able to take young readers down into the leaf litter to see the world with its dangers and its resources from the little frog’s point of view.

This book was about such a rare frog that shortly before publication researchers learned something new about the frog’s life. The illustrator Alan Marks and I decided it was an important discovery. So I rewrote some of the text to have the fictional story reflect this new information, and Alan reworked the illustrations.

So the FACT part of writing faction means it’s important to stay true to sharing what’s real. The FICTION part of writing faction means you need to be aware of a key point about writing any fictional story.

Think of the story as being like a play—told in three acts.

Act One: Sets the story in its location, introduces the main character(s), and sets up the problem to be solved (which may be as real-life as staying alive and successfully raising young).

Act Two: Gives the main character(s) a series of challenges to face and puts them in dangerous situations as they work to solve the problem.

Act Three: Lets the main character(s) face the biggest challenge of all and solve the problem.

In the newly released FAMILY PACK (Charlesbridge, 2011) the faction story opens with a young female wolf alone--on her own—in a strange new world.

This wolf grew up in Canada, was trapped by humans, and released into a new place—Yellowstone National Park. The humans tried to force her to be part of a pack of their own creation, but she wanted no part of that and set out on her own. That, in one page, is Act One.

Act Two follows the young female wolf’s trial and error effort to develop her hunting skills without a pack to guide her and without any experienced wolves to help her catch prey to eat. This act also shows her loneliness when she thrusts her muzzle skyward and howls, but the only answer she gets is an owl’s hoot.

Her hunting skills finally improve. She grows bigger and stronger and gains confidence in hunting in her territory. So much so that Yellowstone is no longer a strange place, it's home.

At the end of Act Two, the young female wolf encounters another wolf, a young male. “Hello, good looking!”

Act Three is romance embodied in learning to hunt as a team. Then the female gives birth to four pups that grow quickly.

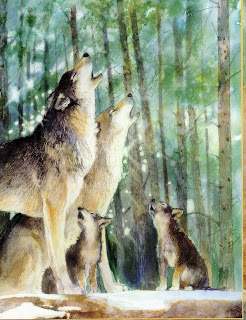

The happy ending is the whole family howling together. “At last, the female is part of a family again—her own family pack.”

FAMILY PACK is faction because while all of the action is imagined, the wolves are real—known to scientists as Female 7 and Male 2. And the way they behaved is based on real wolf behavior. The happy ending to the real story is that When Female 7 and Male 2 found each other and had four pups, their family became the first naturally formed pack following the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in 1995. Called the Leopold pack, it became one of the largest and strongest in the park—at one time numbering twenty-five wolves. And the Leopold pack continues to exist today, hunting the same territory first claimed by Female 7.

Faction is still writing real-life drama, but it's a way to let your imagination spread its wings.

Sunday, February 20, 2011

Thursday, February 10, 2011

WRITING NONFICTION: PART THREE—How Do You Make Your Work Sellable?

Completing the first draft of your book was getting the clay out. Now you’re ready to turn your work into something special—a published book. That process is all about revision. Take that word literally as re-vision. Looking at your work with a fresh mind during each step.

Show Don’t Tell First, go through your text with an eye for showing your reader the action. Nonfiction doesn’t mean a dull lecture. It means real life drama. I love telling the true story of an animal’s life, a rescue from a life-threatening situation, or a scientific investigation that solves a real problem. One of the keys to showing rather than telling is to think of yourself as across the table talking to your reader. And use action verbs.

For example, which of these two paragraphs is more exciting to read?

The wildebeest snort and grunt in panic. Those closest to the water kick and leap, struggling to bound away as the hunter attacks again. This time, the crocodile’s jaws clamp shut on an adult wildebeest.

The wildebeest make panic noises. Those closest to the water run away as the hunter attacks again. This time the crocodile bites an adult wildebeest.

The first paragraph, of course. It’s action is part of ANIMAL PREDATORS: CROCODILES (Lerner, 2004)

Whatever you write, remember verbs are your workhorses. They carry the action, set the mood, and take the reader into the scene. Don’t be afraid to try out different verbs and see how they effect what’s being said.

Read Your Work Aloud Like the chorus in a song, this needs to be something you do after every revision. In fact, it’s good to read your work aloud even while you’re writing the first draft. And that’s true whether your work is thirty-two pages long or over one hundred pages long. I'd hate to count how many times I read aloud the text for Little Lost Bat (Charlesbridge, 2006). My poor husband must know my books by heart because we share an office. I always warn him by announcing, "Okay, I'm going to be talking to myself now."

While you're reading, be sure to listen to what you’re saying. Anything you just naturally tend to leave out, delete. Any words you find yourself adding in, put into the text. If you stumble over a section, rework it.

Remember, your reader is going to hear the words in his or her mind. It really will be as though you're reading your book aloud to that person.

Cut Deadwood Next, go through your work again, checking that you haven’t repeated any concepts or thoughts in slightly different words. Each paragraph, each page, each spread (facing left hand and right hand page) should move the action along.

Change Old Favorites Be careful that you haven’t repeated words and phrases. For example, don’t say “also” or “too” in two or more sentences in a row. Don’t repeat “What if…” in three sentences in a row.

When I’m making this revision pass, I always think of Ernest Hemingway. It’s said that he would rise at 6 a.m. and write standing up at his typewriter until noon. I don’t stand up but I try to put the discipline that required into my revision pass for “Old Favorites”. Besides if your feet were starting to hurt, you’d want to make sure what you were typing was worth having on the page. Of course, Hemingway, it’s said, spent his afternoons in a local bar so don’t spend so long on this revision pass that you feel driven to drink.

Or if, on occasion, that does happen, try a “Papa Doble”, the name of a kind of daiquiri legend has it Hemingway invented one afternoon at Sloppy Joe’s Bar in Key West, Florida. To make it combine two ounces of white or light rum, the juice of two limes, the juice of half a grapefruit, pour over crushed ice and finally float Maraschino liqueur on top.

(Recipe cited here comes from Charles Oliver's Ernest Hemingway A to Z: The Essential Reference to the Life and Work)

Reading Level Know your target audience well. Be sure the language you use expresses what you're sharing in words your readers will know. And the younger your audience the shorter and simpler your sentences need to be. This is also the pass to be sure any new words or concepts are defined or explained where they first appear.

Get An Expert’s Opinion You’re writing nonfiction so what you write must be accurate. You need to contact someone who is an expert on the subject. Ask them to, please, read through your text and make sure what you’re sharing is absolutely correct.

Working through this phase of the revision process always reminds me of the story of the swimming bat. I was working on Outside and Inside Bats (Atheneum, 1997). This was a photo essay and I wanted to include a photo I’d seen in a major magazine, showing a bat swimming. I also wanted to share the fact that bats can swim. After quite a bit of detective work, I tracked down a bat expert who was with the photographer when the photo of the swimming bat was taken. He begged me to not include that information or the photo. He explained that the bat fell into the water and, in fact, drowned after the photo was taken. So while the bat appeared to be swimming it was actually struggling for its life. So always, always check your facts as you write and have your manuscript vetted before you send it out.

Okay, do one more chorus of READ YOUR WORK ALOUD. Then you’re ready to submit your work to a publisher for consideration. Just keep in mind that publishing is a very subjective business. So be willing to revise again to make your work exactly what a publisher wants it to be. I remember an editor who sent me back one of my books for revision with the comment, “I loved page eleven. Make all of the other pages as good as that one.” Happily, I did because that book became the first book in my very successful Outside and Inside series (Atheneum and Walker Books).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

WORLD READ ALOUD DAY FEBRUARY FUN!

Start off this month's FUN by Visiting with me as I share COULD YOU EVER WADDLE WITH PENGUINS! (Scholastic) Now, discover more fun on ...

-

WHAT IF YOU HAD!? SHARE-A-THON Thank you to all you creative people who are finding COOL ways to turn my WHAT IF YOU HAD!? books in...

-

I'm a redhead And I'm proud of it. In fact, being a redhead is a big thing in my family. I have redheaded cousins and a redhe...

-

Dr. Tom McCarthy with snow leopard cub (courtesy of Panthera Snow Leopard Trust) When I can, I love to investigate firsthand. But, when th...